Article extracted from

ESPN soccer net

Flying the flag

No league this weekend of course, due to the European qualifiers. Spain lost 2-0 in Sweden, so no surprises there.

The national team seems to be going through some sort of crisis at the moment, brought on by the traumatic 3-2 defeat in Northern Ireland. Luis Aragonés stated firmly before the game that even in the event of defeat, he had no intention of resigning, a conviction later supported by Angel Villar, the President of the FEF (Spanish Football Federation).

Luis Aragones: Safe in his job

despite predictable defeat

in Sweden.

The truth is that the team are still playing some decent football, but seem to be easily undone by sides that lie in wait and counter-attack, exposing a lack of steel and organisation at the heart of the defence.

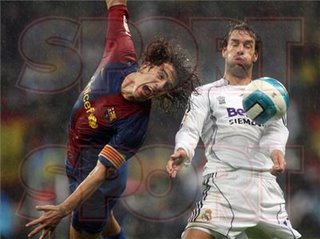

Puyol is all heart, as ever, but has recently began to look less assured when deprived of the cover of club-mate Marquez, and Juanito has never looked very convincing at centre-half. Add to that the fact that Sergio Ramos (who played well) is wasted at full-back, and you have some strategic problems at the heart of the side. Even Casillas is beginning to look mortal. Nevertheless, it looks like a case of good players in abundance, limited by a creaky system.

Two defeats on the trot have certainly put Spain's qualification in the balance, but it's hardly true to say, as Aragonés' fiercest critics are, that Spain can now wave goodbye to the 2008 finals.

I don't know what the viewing figures on national TVE1 were on Saturday evening, but truth be told, the game was partially eclipsed by a match scheduled for the next day in the Camp Nou, between Catalonia and Euskadi (The Basque Country).

Several of the star turns were missing in action, of course, flying home from Sweden. Xavi, Puyol, Lluis Garcia, Cesc, Reina and Xabi Alonso have all played for their respective 'national' sides before, but always in the traditional Christmas matches, when teams from any of Spain's 17 autonomous communities can invite a national team over for a festive friendly.

Not all the communities do - the most active being Catalonia, Euskadi, Navarre, Galicia and Andalucía. Of the five, the former two have historical traditions connected to their '

selecciones' (national teams) going back as far as 1915. In fact, the first ever Euskadi XI made their competitive debut that year against a Catalan XI, beating them 6-1.

Sunday's game was the 10th time in history that the two sides have met, the last time being in 1971 in Bilbao. But the most significant fact about the game was that it was the first time in 67 years that Euskadi had played outside of the Basque Country.

During the Spanish Civil War a team of exiles (all professionals) toured France, Russia, Poland and Denmark (where it secured its biggest ever win, 11-1), moving on to Cuba and then eventually to Mexico, where it enrolled in the national league and won it, in 1939. There's a good trivia question to put a frown on the face of even the most impressive football nerd.

There were more than a few eyebrows raised, however, when the administrative bodies for these two sides put forward a proposal to the FEF to play this game, on the same weekend as official UEFA fixtures. Surprisingly, the FEF agreed, although there are dark mumblings in right-wing circles about pressure from on high.

For the first time in Spain's history, its Prime Minister is a Barcelona fan, although he is not a Catalan. Had the request been made under the previous incumbent, José María Aznar, paid-up Real Madrid member and not exactly the biggest fan of nationalist regional sentiment, the game may well have never come about.

Whatever the truth, since the official announcement that the game would take place, there has been much wailing and gnashing of teeth behind the scenes.

The Spanish right are furious - perplexed that such a brazen act of political nationalist propaganda could take place the same weekend as Spain were playing for the Euro 2008 lives, whilst the Catalan and Basque nationalists have been rubbing it in mercilessly, given a public platform to push their claims for recognition of their national sides.

And of course, it's not really about football. Let's get the cards out onto the table. There's no point in writing about much else this week. If you read this column regularly and are interested in Spanish football, then you need to know these things. Without them, La Liga would lose its spark overnight. The political tensions that underlie almost every match, almost every official act that takes place in the corridors of Spain's football, are directly related to what happened this weekend.

The presence of the Basque Lehendakari (Prime Minister) at the match, shoulder to shoulder with his Catalan counterpart, Pasqual Maragall, both solemnly standing for the two communities' anthems, must have had General Franco turning in his grave, along with several of his present-day acolytes.

For them, Maragall and Ibarretxe, two of the cuddliest-looking blokes you can imagine, are Satan and Beelzebub incarnate. Maragall has put more than a few noses out of line with his reform of the Catalan constitution, bringing even more autonomous powers to Catalonia and using the word 'nation' on the draft - much to the consternation of the Partido Popular (People's Party), now out of power after its mishandling of the Madrid bombings.

Ibarretxe had been putting noses out of line well before Maragall, by insisting on what has become known as his 'plan'. To keep matters simple, he sees a future Basque Country as a nation state, only pulling back slightly on this by his idea of 'free association with Spain', a phrase that has had the mainstream Spanish press snorting over its keyboards ever since.

| “ | The presence of the Basque Lehendakari (Prime Minister) at the match, shoulder to shoulder with his Catalan counterpart, Pasqual Maragall must have had General Franco turning in his grave ” |

|

|

|

Ibarretxe takes it for granted that the Basque Country is a 'nation'. His rather patronising invitation to Madrid to 'keep in touch' has driven the Spanish right wild. What drives Basque nationalists wild (peaceful and less peaceful ones), is that the Spanish constitution forbids them from holding a referendum on the issue. They see this as fundamentally undemocratic, which it probably is.

So, as you can imagine, the game in the Camp Nou had a teeny-weeny bit of symbolism attached to it. Neither Euskadi nor Catalonia are recognised as official national teams, which means that they cannot compete in World Cups or in European tournaments such as the one that Spain played in on Saturday.

They are not the only ones around the globe to be claiming official status, of course, but we suddenly seem to be in the curious position where FIFA has become the granter of nationhood, the arbiter of what can then become (and this is what mainstream Spain fears) the granting of statehood. Give 'em a little, and they'll want more - is the unspoken whisper. Within this framework, there is no distinction between sport and politics - as there never has been, to be truthful.

The 'Balkanisation' of Spain, where the Iberian Peninsula (except Portugal) becomes a collection of small nation-states, was Franco's great nightmare, of course. He may have been right to fear its politico-economic consequences, but he could never deny (or successfully extinguish) its cultural reality.

That's the problem with Spain. It's in a constant state of denial about events such as the Camp Nou on Sunday. 57,000 people went along, making it a major event. Not only that, it was only surpassed by England v Macedonia at the weekend.

But rather than celebrate the plural nature of the communities within its borders, for the entire week before, Spain's sporting and political spokesperson,

Marca, utterly ignored the whole thing, steadfastly refusing to mention it. On the Sunday, they at last gave it some column inches, on page 23, hidden away with news about the Second Division and the regional leagues. Of course, the game subsequently went out on the two regional channels involved. TVE1 ignored it - which neatly underlines the essential problem.

Should these two communities be given official recognition for their football teams? Well, even before watching the vibrant 2-2 draw in the Camp Nou, it's difficult to see how the process can be stopped. Any glance at Spanish history will tell you that it is the concept of 'Spain' as a nation that is far more vague and convoluted than the idea of Euskadi and Catalonia. They were both around long before, as were their languages.

As Diego Torres wrote in

El Pais: 'Because there is no consensus over the nature of the Spanish state, there is no consensus over the national team.'

Bingo. Spanish international players have complained for decades that the country is not really behind them, as a whole, and that when the squads have been Catalan and Basque heavy, the politically schizophrenic nature of the team has too often come to the surface.

There's nothing like patriotism to stir on a team - but without it, Spain's mysterious under-achievement over the years (given the quality that has stalked its ranks), is difficult to explain away on any other grounds.

Myths abound.

'La Furia Española' (The Spanish Fury) is a legend that implies that its teams have been traditionally tough, full of no-nonsense characters ready to die for the cause. The phrase dates back to 1920 when the team took the silver medal at the Antwerp Olympics, after a bloody battle against the Swedes.

The problem with this phrase, still used by the Spanish press today, is that of the eleven players in the team that day, nine were Basque and the other two were Catalans. Calling this the 'Spanish' fury is, let us say, rather dodgy on cultural grounds, and yet the phrase lies at the heart of Spain's footballing identity.

| “ | Because there is no consensus over the nature of the Spanish state, there is no consensus over the national team. ” |

|

| — Diego Torres |

A parallel would be to imagine that the United Kingdom had never been called as such, and had just been called 'England'. In terms of the constitutional powers traditionally granted to 10 Downing St, it might as well have been.

Imagine them winning the World Cup, with nine of the players from Scotland and two from Wales (for example), and the victory forever referred to as 'English'. That is essentially what has happed in Spain.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Island have been devolved greater powers in the past few years, but they still possess less autonomous legislative powers than the Basque Country and Catalonia. That's a fact. It's just that Spain has continued to call itself 'Spain', instead of calling itself the 'United Kingdom of Iberia' or something - with apologies to Portugal.

The fact that those three countries can play in the World Cup and Euskadi cannot is a conundrum that needs solving. Euskadi's 'free association' with Spain would simply mean that its players could choose who they wanted to play for, and that would be an end to the matter. There's not enough space here to compare other anomalies (The Faroe Islands for example) with the denial of official status to the two communities under the microscope, but there is a twist to this tale.

My friend the barman reckons that the granting of official status to teams like Wales and Scotland (in a variety of sports) has actually given those nations a focus, and given them a conduit for their patriotism - lessening the chances of terrorism and nationalist mayhem. Northern Ireland is a more complex case, but it's an interesting thought.

Because if the barman's right, then the granting of similar footballing status to such traditionally awkward chaps as the Basques and the Catalans might have the same effect - and not only that, it might eventually lead to the strengthening of the concept of what is 'Spain' - with those two funny regions speaking funny languages finally placated and playing each other in the World Cup final (in Madrid?) - having just beaten Tibet and Gibraltar in the semi-finals.

To conclude this tricky issue, it all depends on whether you view Sunday's game as a unifying or a divisive act, and everyone's entitled to their opinions.

Football could eventually save Spain from itself, but only if people are prepared to sit around the table.

That, unfortunately, has never been easy here.